Archivio

C’erano una volta Baudrillard, un robot e dieci scatole di Montana…

Mi sto passando le librerie indipendenti e nuove edicole, per lasciare in giro qualche copia della mia zine AI: Il Bufo. E ieri ho preso qualche rivista d’arte per capire meglio il discorso delle recensioni del writing che stiamo facendo da un mesetto. Alla fine oggi, mesmerizzato dalla rivista di graffitismo, ho provato a fare una recensione dello street artist Jo di Bona, sullo stile delle recensioni di Greg Tate per il Village Voice (capolavori che si trovano un po’ anche online e su questo bel sito). Ovviamente è un mega risultato dozzinale che non si può tradurre, fatto con il ChatGPT sia per il pastone di riferimenti culturali sia per la stesura del pezzo (ci ho messo a mano un po’ di sbrilloni, Go Transcript dice che sono 55 edit con un 11% di cambiamento sull’output della macchina). A prestissimo amici!!!

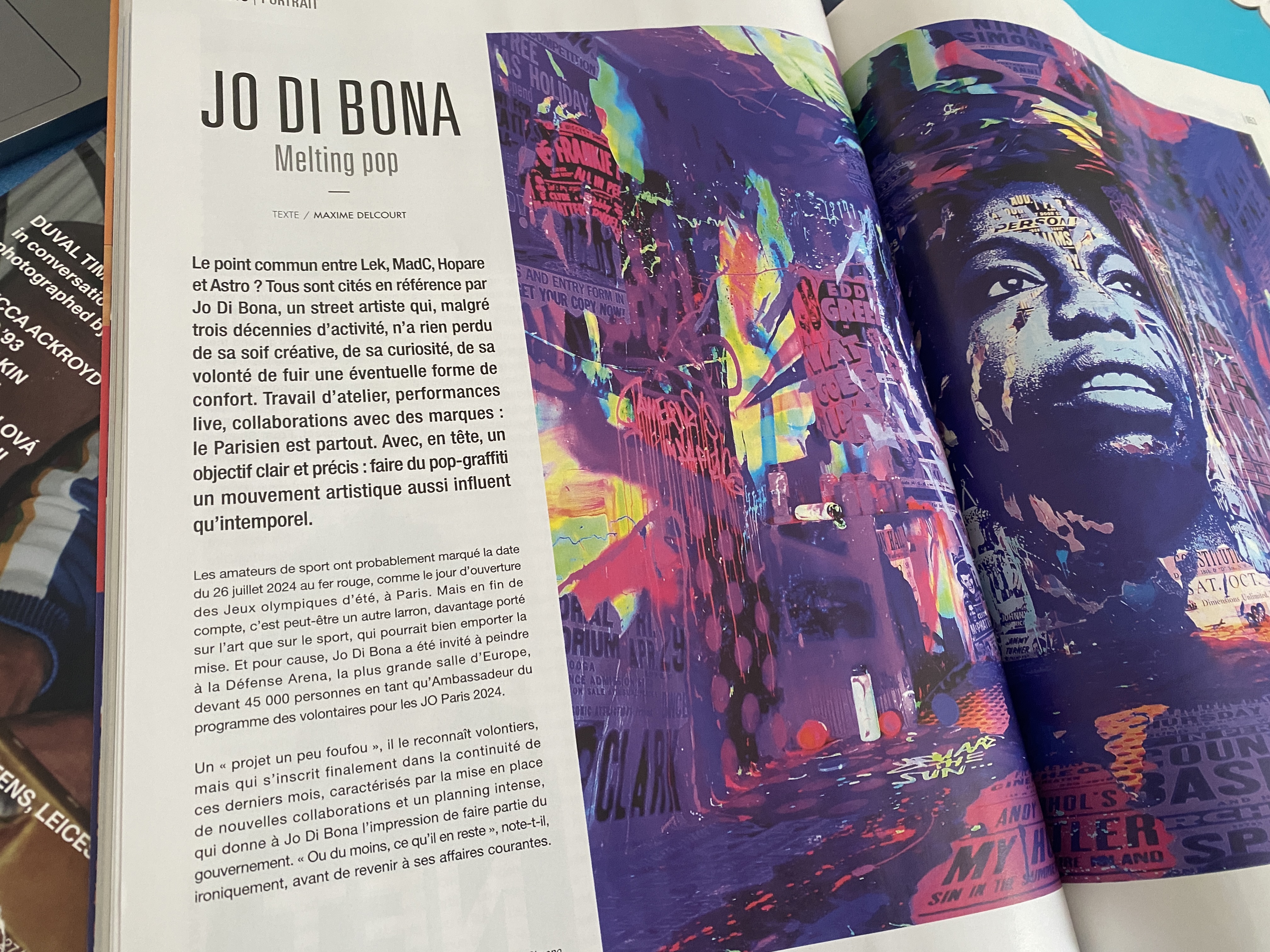

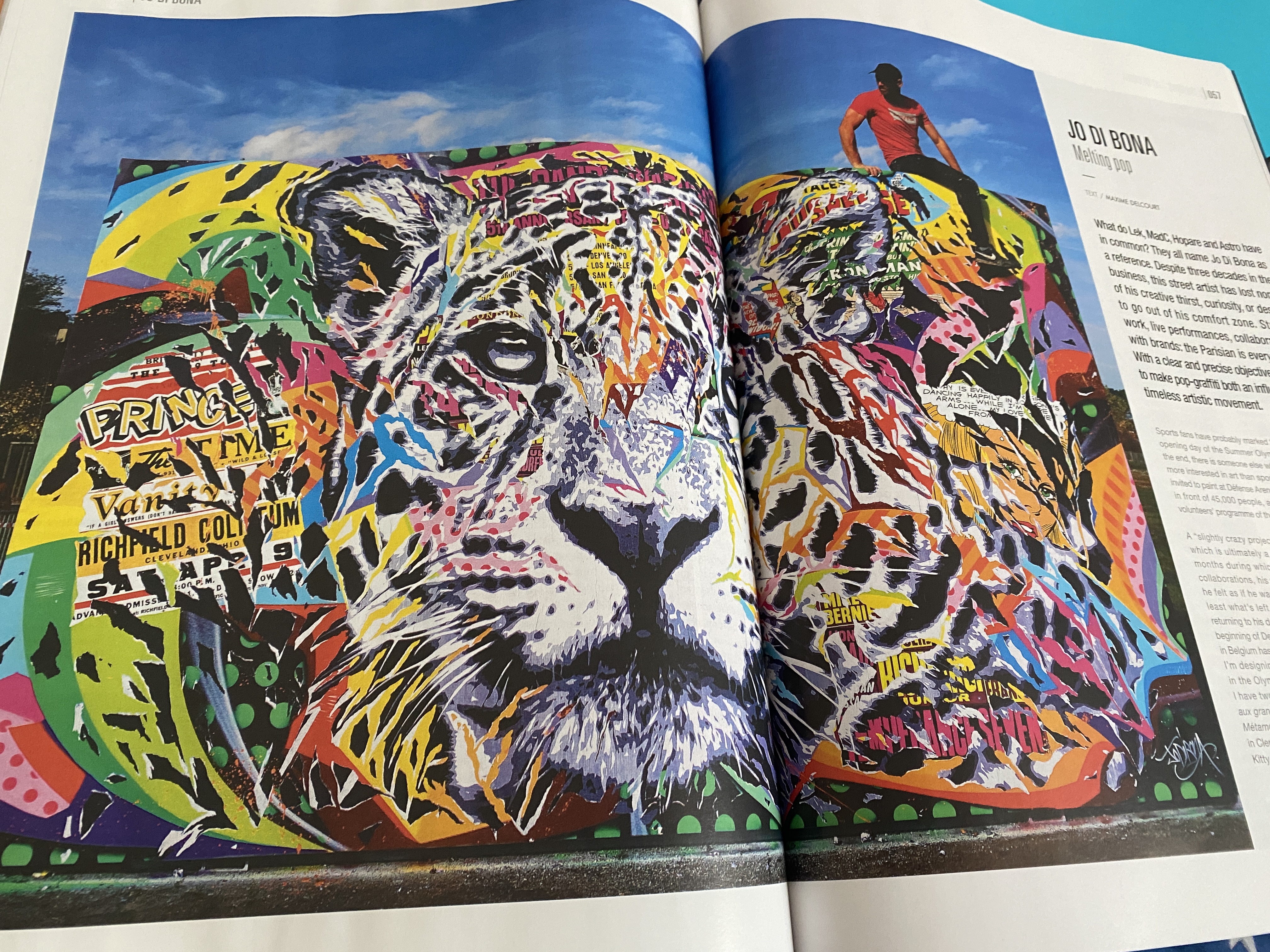

In the crisscross world of eye candy that Jo Di slings, we’re puppets in a whirlwind—caught between ‘damn, that’s fly’ and ‘but what’s it really saying, though?’ This is art in the age of the double-tap, where aesthetics are shotgun-married to the instant gratification of a scroll. Di Bona, with his million pixel dreamcoat of visuals, ain’t just painting pictures; he’s serving up smoothies—those over-foamed, under-nourished concoctions of our era, all swagger with no bite, a hip-hop track watered down just enough to play in the background of a bougie supermarket.

It’s like, what happened to the scratch of vinyl, the grit in the voice? Back in ’87, rap was ripping up the rulebook, mashing up linguistics, a schizophrenic deviant. That was the hunger, the thirst, our will to kill the senseless. Now, Di Bona’s throwing everything into the blender—JFK (or is this MLK), Gainsbourg, you name it—hoping a patchwork of Shutterstock and Pins will spearhead the greater good. All surface, no surf. A Chinese bakery where only the fortune cookie is left on display: for something more substantial, try pizza around the corner.

Here’s the kicker, though: ain’t this the very essence of our shampoo-slick society? We’re in the era of the visual supermarket, where every image is just another item on the shelf, snacked and scrolled in the blink of a red fish eye. Bourdieu might’ve said something about cultural capital, but what’s capital in a world where the middle class is as hollowed out as a busted speaker, and highbrow’s just another aisle in the store?

Now, on to AI: the epitome of this whole shebang—art that’s as nutritious as frictionless foam, as engaging as a dead channel. Jameson saw it coming, the whole postmodern pastiche thing, but damn, did he know it’d get this sterile? Adorno’s probably spinning in his grave, witnessing the regurgitation of ‘culture’ that’s as individual as a barcode. Absolute oblivion as a goal. The big mural reassuring the population there’s no need whatsoever for any kind of “brain supplement”. If it’s not propaganda: let’s call it sneaker culture and that’s it.

So, when Di Bona slaps Nina Simone on a wall, is he sparking thinkpieces or dressing windows for high street Christmas? His art don’t challenge, it don’t question. It’s as deep as a puddle in Death Valley. This is Baudrillard’s Disneyland, where the map’s become the territory, and everything’s so damn pretty, we’ve forgotten to ask where the hell we are.

Reframing the coolness of midmarket consumerism? Cognitive low carb as new minimalist aesthetic? Semantics as cholesterol for our minds? Yeah, horizon scanning for plenty new critical tricks… But fret not, my friend! Let’s ride the carousel together, pretty as a picture, empty as the promise of tomorrow in the land of perpetual now. Until Poptimism is old fart, maybe we can just pretend it’s all a drink of fresh water, not a Waterloo…

Doze Green: recensione e prova d’ascolto

L’altro giorno l’artista G. Spazio mi ha provocato con una traccia pazzesca. Doze Green rispetto a Joan Mirò: “Non so se tu hai presente la statua di Mirò che si trova sulla circonvallazione interna, quella che passa dietro San Babila e va verso via Manzoni. Ecco vedere quella statua ti fa comprendere Doze.” Senza saperlo, Giacomo ha colpito un punto nevralgico della mia psiche traballante: per anni quella statua mi era passata inosservata. E per altri lunghi anni, avevo cercato di capire il significato di un mostro surrealista nel pieno centro della Milano neoclassica. Un senso ci doveva essere.

Così mi sono arrovellato per un paio di giorni. Se Spazio mi diceva: “Il mondo di un artista visuale è complesso. Se alle spalle c’è non solo la necessità urgente di esprimersi, quello che non si vede è altrettanto interessante poiché imprime una direzione al suo lavoro.” Allora era imprescindibile e divertente scartabellare nell’invisibile. Giocare a fare il critico d’arte e pestare la testa nel muro, girellando al buio tra via Senato, Maiorca e il Caribe.

In superficie, il rebus è facile: le figure zoomorfe dei due artisti sono le stesse. Doze cita spesso le avanguardie di inizio secolo: è un dialogo tra artisti al di là dello spazio-tempo? È un campionamento rap che ha il sapore di omaggio e ruberia? O hip hop come avanguardia della società di oggi? È l’occhiolino al gallerista, per dare al pubblico un gancio di comprensione facile, un contesto di arte alta per uscire finalmente dalla cornice antiquata del writing? Chi lo sa, chi se ne importa. La questione è altra.

Una delle poche pagine web che descrive bene Doze è quella dell’esposizione Modulaciones della Colección Isabel & Agustín Coppel, in Messico e qui. “Per l’artista, il passaggio dalla strada alle gallerie non ha cambiato il significato del proprio lavoro: raccontare le storie degli oppressi e l’incertezza della loro vita.” Fin qui tutto normale. Ritrovo lo stesso significato nella statua di Mirò, dal ciclo del Re Ubu con cui aveva dipinto la dittatura franchista. Nella Collezione permanente della Fondazione Arnaldo Pomodoro si definisce quintessenza della cultura “contro”.

Ma il Re Ubu surrealista era una liberazione dalle convenzioni sociali, una fuga dal mondo soffocante dell’Europa moderna che stava perdendo di senso. Gli strumenti erano l’assurdo, l’allucinazione, il sogno. È qui che Doze Green diventa altro, grazie alla sua preziosa esperienza nera. La scheda sul sito messicano continua: “Così, nelle sue opere sono presenti figure che corrispondono a esseri di antiche civiltà e culture indigene, comprese le sue radici afro-caraibiche. A volte queste figure emergono in contesti apparentemente futuristici, con messaggi che mirano ad attivare il potenziale della sua comunità.”

Doze non ha da fuggire, i canoni della sua cultura afrodiscendente sono qualcosa di sacro, da proteggere e comunicare, utile a fondare la scoperta del nostro futuro. Forse potremmo definirlo Rasta: il sistema capitalista di Babylon è un’immane orrore, ma come nemico diventa un nostro limite. Meglio abbandonarlo tout court: c’è una ricchezza infinita cui attingere nel cosmo. Non c’è una liberazione da raggiungere: è già raggiunta, nelle Sacre scritture si chiamava Revelation. “The gates of Zion are open wide, so won’t you come inside,” come diceva Junior Byles. Certo, magari è più facile capirlo in una fattoria autosufficiente in qualche campagna americana.

I surrealisti volevano andare oltre alla metafisica e per questo si erano inventati la patafisica. Era il loro strumento critico verso un mondo accademico rigido e stantio, la scienza delle soluzioni immaginarie. Doze la soluzione la ha già in mano, la metafisica è perfettamente sufficiente. Il campo di gioco di Mirò è teatrale, quello di Doze è cerimoniale: sogno e follia diventano, per nostra fortuna, sogno e magia. I galleristi amano parlare dei suoi teriantropi, gli uccelli umani che officiano alla trance comunicativa tra i diversi mondi, nelle religioni della diaspora africana. I paroloni dell’antica Grecia nobilitano tanto, ma non ci servono a niente. Basterebbe parlare di più di queste linee bianche che connettono le sue figure: sono l’energia invisibile che ci lega tutti? Io credo di sì.

I’m playing art critic for fun: aerosol art and its descendants apparently are not that well covered online, so I feel there’s some room to experiment. Above is a tribute selection by Cyrus, below is some machine translation of my piece.

Yesterday, fellow artist G. Spazio provoked me with a crazy hint. Doze Green & Joan Miró: “I don’t know if you’re aware of the statue by Miró that is on the inner ring road, the one that goes behind San Babila and goes toward Via Manzoni. That statue makes you understand Doze.” Without knowing it, Giacomo hit a nerve in my shaky subconscious: for years that statue had gone unnoticed while passing by. And for many more years, I had strived to understand the meaning of a surrealist monster in the middle of neoclassical Milan. Some meaning there had to be.

So I racked my brains for a couple of days. If Spazio told me, “The world of a visual artist is complex. Behind the artist, there’s not just an urgent need for expression, what is unseen is just as interesting because it imparts a direction to his work.” At that time it was for me inescapable and fun to scrabble in the invisible. Playing art critic and hit your head on the wall, while wandering in the dark between via Senato, Majorca and the Caribbean.

On the surface, the puzzle is easy: the zoomorphic figures of the two artists are the same. Doze often cites the turn-of-the-century avant-garde: is this a dialogue between artists, beyond space-time? Is it rap sampling that has the flavor of homage and piracy? Or hip hop as cultural avantgarde? Is it a wink to the gallerist, something to give the audience an easy understanding and a high art context, to finally break out of the antiquated framework of aerosol writing? Who knows, who cares. This is not our main question mark.

One of the few web pages that describes Doze well is that of the exhibition Modulaciones at Colección Isabel & Agustín Coppel in Mexico. ” For the artist, the change from producing his art on the street to taking it to galleries has not changed the meaning of his work, which tends to tell the stories of oppressed people and the uncertainty of their lives.” So far so normal. I find the same meaning in Miró’s statue from the King Ubu cycle with which he had painted the Franco dictatorship. In the permanent collection of the Arnaldo Pomodoro Foundation it is called quintessence of counterculture.

But the Surrealist’s King Ubu was a liberation from social conventions, an escape from the suffocating world of modern Europe that was losing its sensemaking abilities. The tools were the absurd, hallucination, dreams. It is here that Doze Green becomes something else, and his invaluable black experience is of the essence. The Mexican exhibition site continues, “Thus, in his work there are figures who correspond to beings from ancient civilizations and indigenous cultures, including his own Afro-Caribbean roots. Sometimes —as is the case with Rock the World— these figures emerge in seemingly futuristic contexts, with messages that aim to activate the potential of his community.”

Doze has no need for escapism; the canons of his Afrodescendant culture are something sacred, to be protected and communicated, useful in grounding the discovery of our common future. Perhaps we could call it Rasta: the capitalist system of Babylon is a big disgrace, but as an enemy it becomes our limitation. Better to abandon it tout court: there is infinite wealth to draw in our cosmos. There is no liberation to be achieved: it is already achieved; in the Holy Scriptures it was called Revelation. “The gates of Zion are open wide, so won’t you come inside,” in the words of Jamaican singer Junior Byles. Of course, maybe it is easier to understand when you’re living on a self-sufficient farm somewhere.

The Surrealists wanted to go beyond metaphysics, so they came up with pataphysics. It was the critical tool to oppose a rigid and stale academic world, it was the science of imaginary solutions. Doze already has the solution at hand; metaphysics is perfectly sufficient. Miró’s playing field is theatrical, Doze’s is ceremonial: dream and madness become, luckily, dream and magic. Gallerists love to talk about his therianthropes, the human birds who officiate at the communicative trance ceremonies between different worlds, in the religions of the African diaspora. Using the high sounding words of ancient Greece ennobles so much, but it does us no good. It would suffice to talk more about these white lines that connect his creatures: are they the invisible energy that binds us all? I believe they are.

Recensione e prova d’ascolto: Dondi + Aeron

I nerd dell’aerosol art conoscono e adorano il libro Style Master General, monografia di uno dei writer più stilosi di sempre, Dondi White. In quelle pagine ci si bea di pezzate celestiali, classiche come l’arte dell’Antica Grecia, belle come l’hip hop dei primi anni ’80 che non tramonterà mai nei nostri cuori.

Sull’onda di sta cosa della sonorizzazione del writing, ho tampinato Cyrus (colui che ascoltò 50 mila album) e Vanni (colui che resse il pranzo della domenica dai suoceri): dieci tracce a testa (qui io, poi Cyrus e poi Vanni), una playlist per uno e proviamo a stare su questo treno del 1981 dallo speciale di Spraymium. Quindi, se vi va, beccatevi la nostra idea musicale che è un tributo a Dondi White: grazie leggendario maestro, ogni volta i lacrimoni con ste foto. No anzi, l’energia infinita…

Ho fatto anche un tentativo di recensione da critico d’arte: è la mia fissa di adesso. Le citazioni colte partono da name dropping pesante di G. Spazio, che ringrazio. Mia figlia mi ha detto: Ma papà, aspettà un secondo, ma proprio con Dondi? Ma non puoi prendere qualcosa di un tuo amico, così ti fai meno male… Ma no Ceci, perché, facciamo bungee jumping con il mio equilibrio psichico, è più divertente… o la va o la spacca…

Scroll at the bottom for a machine translated English version of my art critic fun test.

Un classico lo riconosci perché piace a tutti. Dondi è questo per l’aerosol art: il più amato dai writer, il più ricercato dai collezionisti, il più fotografato nei primi libri mass market che hanno lanciato il writing in tutto il mondo.

I suoi whole car Children Of The Grave sono un simbolo universale dell’hip hop dei primi anni ’80: il puppet di Bodé che mangia la mela e la mano tesa al cielo, le lettere morbide, le palette pastello. Probabilmente i treni più famosi di sempre. Forse lo spartiacque con la nuova generazione che era stata l’ultima a fare i whole car, prima che i treni venissero puliti in maniera massiccia. Siamo nel ’78-80: Dondi aveva preso le consegne da maestri come Lee, dai loro whole car figurativi che avevano il sapore del muralismo latino americano. Spiriti liberi, citazioni libertarie hard rock, i grandi temi sociali delle inner city terzomondiste. I writer pescavano a piene mani dal mondo dei fumetti: facile farsi capire dal grande pubblico dei pendolari sulla subway, facilissimo fare cose belle senza essere veramente fumettisti. Nella coscienza collettiva è rimasto questo ed è qualcosa di molto diverso da quello che hanno nel cuore i writer.

Il punto di frattura: ai writer non serve un’analisi verbale, al grande pubblico sì. Ma critici d’arte e giornalisti si sono spinti raramente oltre a pochi luoghi comuni: il gesto illegale, la performance esotica, il grido di redenzione che erompe dalla periferia. Anche nel passaggio alle gallerie d’arte, lo stereotipo resta un terreno sicuro: se il writer si limita a dipingere i suoi pezzi su tela è meglio, molto facile da capire per il collezionista, “molto vero”. Lo racconta Edit deAk nella recensione del 1983 per Artforum della mostra di Dondi alla 51X Gallery: “Questo scoraggia l’artista dal cercare adattamenti da un campo di gioco visuale a un altro del tutto nuovo.” Al nuovo pubblico dell’arte tradizionale, Dondi presenta figure stilizzate, sketch che raccontano la vita di quartiere: “gli amici, i personaggi, gli sguardi, i ricordi personali”. Ma anche qui siamo nel dominio del figurativo, di opere create per un pubblico diverso, per le persone normali.

Se parli di Dondi con un writer, probabilmente finirai a parlare di panel pieces, di window down, dei pezzi più piccoli che spesso eseguiva in coppia con un amico, disegnando lui i bozzetti per tutti. E’ qui che trovi il nocciolo duro della faccenda, la purezza della cultura: quando senti parlare di style writing, è questo. La sensazione è sempre quella morbida e pastellata dei whole car, ma i cartoon questa volta non arrivano dalle edicole e dalla tv. Sono completamente originali e fatti di lettering: semi wild style e wild style. Il soprannome di Dondi era Style master general: Lady Pink diceva che suonare come Hendrix e dipingere come Dondi è un sogno, una fantasia impossibile. Per trasmettere la forza della sua impronta stilistica, basti pensare che la scena europea esplosa a Parigi e Amsterdam nell’84-85 arrivava in buona parte da lui e dalle sue crew, TOP e CIA. Dondi è facile, elegante, sofisticato. Trasuda self confidence, ha un gesto rapido e pulito. Dondi è famoso perché disegna con una dedizione assoluta, i suoi outline sono meticolosi fino alla perfezione.

Ma, nel deposito, ha una execution da arti marziali: il tempo a disposizione e la luce sono pochi. Devi dipingere senza accendere il cervello, hai solo i sensi amplificati al massimo e l’istinto. Dipingere è una questione di velocità, di combattimento. Il giorno dopo, l’incertezza si vedrebbe subito. E’ qui che vedi il maestro: la fulmineità del gesto creativo che deriva dall’intelligenza, come diceva Emilio Villa: “Parlarono della pittura come gesto, il gesto della pittura. Qui credevano che il gesto consistesse nel fare così… pennellare col gesto, capito? No, il gesto era un fatto interno, un fatto pensoso che prima di muovere era mosso dal pensiero”.

In un’epoca di AI che sa riprodurre tutto, forse è questo il concetto prezioso da portarsi a casa. Puoi ripetere per filo e per segno i formalismi di Dondi: sarai uno dei tanti manieristi di oggi, tecnici e perfettamente in stile, vuoti. Questo lo vediamo fare progressivamente sempre meglio anche alle macchine. E’ lo spirito del maestro quello che ti segna, è lì che sta l’arte, “la scienza che sa ancora di magia”. E questo forse non serve spiegarlo a parole, perfortuna.

A classic is something you recognize because everyone likes it. In the aerosol art domain, Dondi embodies this universal acclaim: the most beloved among graffiti writers, the most sought-after by collectors, and the most photographed in the pioneering mass-market books that introduced graffiti to a global audience.

His “Children Of The Grave” whole cars are an iconic representation of hip hop in the early ’80s: Bodé’s puppet munching on an apple and a hand stretched towards the sky, soft letters and pastel palettes. These are arguably the most famous trains ever. They might also represent a turning point for the last generation that engaged in whole car graffiti before massive clean-up efforts began. During 1978-1980, Dondi picked up the baton from masters like Lee, whose figurative whole cars carried the flavor of Latin American muralism. They incorporated elements of free spirit, hard rock libertarian quotes, and the major social issues of the inner-city. Writers heavily drew inspiration from the comic book world, making it easy to communicate with the broad commuter audience on the subway, effortlessly creating beautiful works without being professional comic artists and illustrators. This legacy has remained in our collective consciousness, marking a departure from what real writers hold dear.

The divide lies here: while graffiti writers may not seek verbal analysis, the general public does. However, art critics and journalists have seldom moved beyond a few clichés: the illegal act, the exotic performance, the outcry for redemption bursting from the outer boroughs. Even as aerosol art made its way into art galleries, stereotypes continued to offer a safe haven. Limiting writers to painting their pieces on canvas was deemed preferable and easier for collectors to understand, “very real,” as Edit deAk pointed out in her 1983 review for Artforum of Dondi’s exhibition at 51X Gallery. This discouraged artists from seeking adaptations from one visual playing field to an entirely new one. For the new traditional art audience, Dondi presented stylized figures and sketches depicting neighborhood life “friends, characters, glances, personal memories.” Yet, even here, the work remained figurative, designed for a different audience, for ordinary people.

When talking about Dondi with a writer, the conversation likely shifts towards panel pieces, window downs, the smaller works he often executed with a friend, drafting sketches for both. This is where you find the inner core of the matter, the purity of the culture: when you hear about style writing, this is it. The feeling is always that soft, pastel vibe of his whole cars, but the cartoons this time are not from newsstands or TV. They are completely original, made of lettering: semi wild styles and wild styles. Dondi was known as the Style Master General: Lady Pink remarked that playing like Hendrix and painting like Dondi was an impossible dream, a fantasy. To convey the strength of his stylistic imprint, consider that the European graffiti scene that burst onto the scene in Paris and Amsterdam in 1984-85 was largely influenced by him and his crews, TOP and CIA. Dondi’s style is effortless, elegant, sophisticated. He exudes self-confidence, with a gesture that’s fast and clean. Dondi is renowned for drawing with absolute dedication, his outlines meticulously perfect. On the Internet, it’s been defined as monastic.

But in the train yard, his execution resembles martial arts: time and light are scarce when you’re bombing. You must paint without engaging the brain, relying solely on heightened senses and instinct. Painting became a matter of speed, it’s like fighting. Any uncertainty would be immediately noticeable the following day. Here, you witness the master: the rapidity of the creative gesture that stems from intelligence, as Emilio Villa put it: “They spoke of painting as gesture, the gesture of painting. Here, they believed the gesture was to do this… paint with a gesture, understand? No, the gesture was an internal affair, a thoughtful act that was moved by thought before movement.”

In an era where AI can replicate everything, this might be the precious take away. You can replicate Dondi’s formalisms to the letter: you’ll be one of many contemporary mannerists, technically proficient and perfectly stylish, yet void. This is something machines are progressively doing better as well. It’s the spirit of the master that marks you, that’s where art lies, “the science that still tastes of magic.” And perhaps, fortunately, this doesn’t need to be explained in words.

Commenti recenti